Huda Sultan: The Power of Captivating Charm

In a Kantian worldview, there’s a strict divide between beauty and brains; being beautiful is a mere privilege, while being clever is a serious chore of constantly pursuing further knowledge. In this light, if we presume that the art of seduction relies heavily on beauty alone, then a woman seeking to pursue a man must sacrifice her wits in the process.

This aspect of Kant’s logic was adopted by Hollywood and its Arab counterparts when it came to casting female roles. On the silver screen, a clever woman might be able to intrigue a man, but she cannot truly entice him. She must therefore resort to playing wicked games and luring him into sinful pleasures.

In black and white cinema, seduction takes on many forms that usually revolve around wit. But not all wits are the same; between natural intelligence and acquired intellect is a world of difference, just as there is between Faten Hamama, Magda and Lubna Abdulaziz on the one hand and Huda Sultan on the other. This difference can be summarized as a difference between clarity, maturity, and open-mindedness, as opposed to emotional intelligence, empathy, and desire.

Even early on in Huda Sultan’s career, just after her second feature film, director Hasan El-Imam noted, “this woman is a magnet; she might be shy in front of her musician brother Mohammad Fawzi, but never in front of the camera! She hits like a melody, a symphony, a masterpiece”.

|

But what is the secret behind Huda Sultan’s charm? Why her and not Berlenti Abdulhamid, the infamous temptress despite her short-lived career? Why not Hind Rustom, who was after all nicknamed “the star of temptation”?

Perhaps part of Sultan’s charm is that she almost exclusively played working class characters, while Rustom’s roles were scattered along a wider spectrum of socioeconomic classes. Rustom was undeniably beautiful, sexy, and delicate; her seductive methods were marked by a hint of narcissism that is not without an intriguing wit. And although Sultan was not nearly as beautiful in an absolute sense, she pioneered in the art of seduction, and navigated the temptress trope more boldly than any other. Huda Sultan dared to venture into uncharted territories, and that was where all the magic happened.

THE TEMPTATION PHASE

In Niazi Mostafa’s 1958 The Midnight Driver, Huda Sultan played the “ma’allema”, a stereotypically stern female character, whose toughness is enhanced by a loose dark robe and a black headcover. While this role was not the one to launch her to stardom, it definitely framed her as a seductive protagonist, even when her conservative costume concealed her flesh, and with it her bodily hunger to tap into a world of desires.

In film, temptation and flirtation are employed in various ways, of which seduction is always part and parcel. On-screen seduction typically carries a lot of sensual connotations, bringing to mind countless bar scenes whereby a background performer would stand attractively, not uttering a single word, but speaking volumes with her body and her eyes. Such scenes are usually paired with soundtracks that are designed to eroticize superficial beauty; the whole act is conducted briefly and deliberately to capitalize on pure pleasure.

Huda Sultan, however, exercised her charm within the confines of the “local townswoman” character, only rarely outstepping it. This role is always burdened with nuanced complications, especially since the customs and traditions that are upheld in towns, villages, and neighborhoods are unforgiving of women who choose to break taboos and stray from social norms. And it is often through these women that the hypocrisy and the contradictions of society are exposed.

|

Due to the many complications within and around her, the “local townswoman” will naturally find herself in the face of conflict. In these situations, Huda Sultan’s characters appear like clouds in a clear sky; they storm right through, and bring about the rain.

The nuanced townswoman character cannot afford to tread fine lines when there are barriers she must jump. Her tone is firm and assertive, with a hint of reckless aggression, even when speaking to her own lover. Her lines require great talent and strong intuition to be delivered properly. Perhaps Huda Sultan’s most memorable roles in this regard are Nazha from Platform No. 5 (1956), Sharbat from End of the Road (1960), Baheyyah from Arms Market (1960), and Tawhida from 3 Women (1960).

FEMININE ATTRIBUTES

In the early 1950s, film stars followed more or less the same beauty standards. From Hollywood to Cairo, female protagonists were necessarily delicate, fragile, slender, and lenient. But Huda Sultan dared not to fit the mold.

Instead, Sultan introduced a more authentic set of standards that fits the local feel of her characters: she stood tall as a mountain, with wide shoulders, and a plump figure. Her strong build was consistent with that of her male protagonists, including Farid Shawqi, Rushdy Abaza, Imad Hamdy, and Yehia Shaheen, and less so with others such as Shukry Sarhan and Salah Zulfikar. In most cases, Sultan’s plump figure highlighted her confident sense of possessiveness over her beloved man, especially in the context of seduction.

|

Whether acting or singing, Huda Sultan’s performance was marked by a visible yearning. She would glance at her lover as her muscles tremble with burning desire, her figure swaying to the rhythm of her speech, until he finally surrenders and succumbs to her will.

In addition to her physique, Sultan also had a unique hairdo, which was neither straight, wavy, nor curly, but rather altogether unruly. Of course, it must be no coincidence that a rebellious character would have untamed hair, representing her indifference and her wilderness.

|

Another aspect of her charm also lay in the sound of her laughter, which was effortless and husky, as opposed to the clichéd attention-seeking shrieks.

On the level of fashion, Sultan usually appeared in satin robes wrapped tightly around her wide waist, with tassels hanging from her shoulders, therefore revealing her seductive powers upon the first glance.

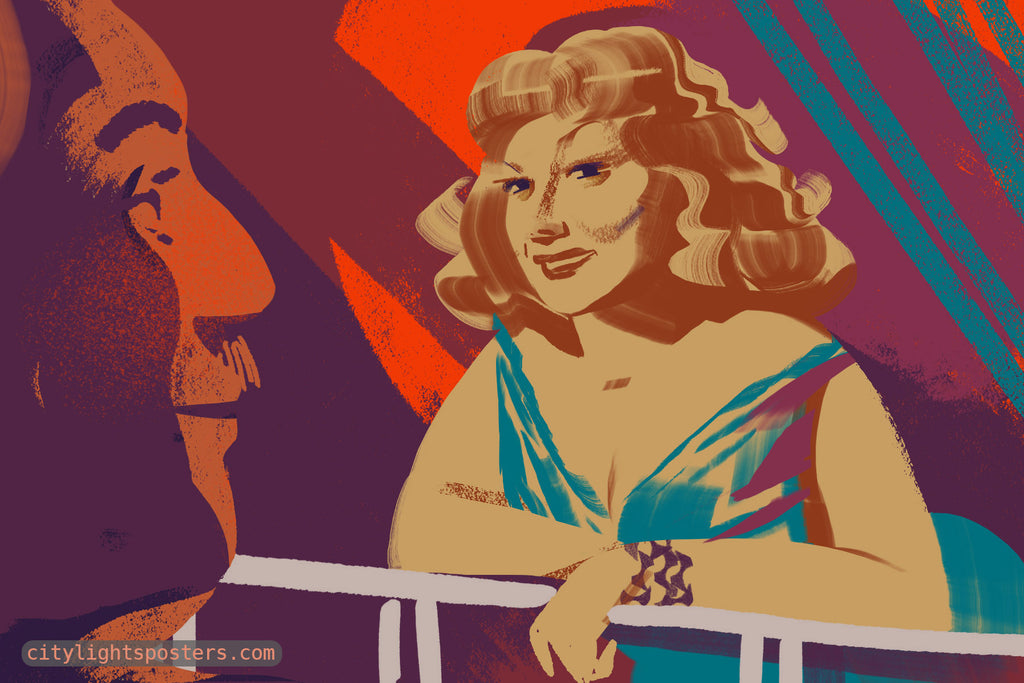

In Love and Flirtation, Sultan stands on the balcony wearing a silk dress that reveals her curves as she invites a 60-something Hussein Riyad upstairs for coffee, describing its flavors with a voice that is at once sober and dreamy, before playfully blowing the old man a kiss. The next thing he knows, he is in his office, scolding one of his employees for bringing him tasteless coffee; just like that, he began to lean, his doubts would soon fade, and this woman would eventually bind him to an eternal hell.

PLAYING WITH FIRE

Although most female film stars preferred to steer clear of this role in favor of being cast in the shoes of “the innocent girl”, Huda Sultan never shied away from playing the temptress. She was not discouraged by the sensitive and problematic nature of the role, nor was she put off by the moral policing of film plots such that the temptress is almost always outcast physically and morally.

It is no doubt risky business for a woman to pursue her husband’s brother, or to woe his friend, or to become the mistress of her daughter’s fiancé, but Huda Sultan pulled of all such scenarios in a span of three years, most remarkably in Woman on the Road (Izzeddine Zulfikar, 1958), Forbidden Women (Mahmoud Zulfikar, 1959), Love and Flirtation (Mahmoud Ismail, 1959), Wife from the Street (Hasan El-Imam, 1960), and The Lover (Sayyed Ziyadah, 1960).

|

In other films, Sultan’s seductive powers are rooted in the context of her character, which usually represents those on the fringe of society: the underdogs, the belly dancers, and the wedding singers. Sultan skillfully masks the motives behind her character’s lifestyle choices, often creating a distance between what she hides and what she reveals, thereby offering a useful key to plot development. In such films, we often see Sultan carrying her sorrow within as she searches for a safe harbor, as is the case in Kahraman (Elsayed Bedeir, 1958), Men's Huntress (Hasan El-Imam, 1960), and The Secret of a Woman (Atef Salem, 1960).

NATURE TAKES ITS COURSE

After making a name for herself on the silver screen, Sultan geared towards theater. This coincided with the rise of a new generation of female film stars, including Soad Hosni and Nadia Lutfi, and later Mervat Amin, Suhair Ramzy, and Naglaa Fathy in the 70’s.

However, Sultan still appeared in a number of films where she could act her age, including Egyptian Dalal (1970), The Choice (1972) and Masters and Slaves (1978). Sultan seemed to make her peace with the natural progression of her career. Slowly but surely, she morphed from an object of desire into a motherly figure, in film and television alike.

|

Most importantly, she did not isolate herself like Nadia Lutfi, nor did she completely retire in protest to the production industry like Hind Rustom. Instead, she managed to affirm her captivating presence, as she did indeed in The Return of the Prodigal Son (Youssef Chahine, 1976), as well as in the 1980 television series Zaynab and the Throne.

CAPTIVATING TILL THE END

During the early 80’s, when Sultan was being cast in a lot of motherly roles, she was asked in an interview whether there was a certain outfit that brought her good luck, and she replied, after a brief pause, “I don’t think it’s about luck, but I’m very fond of the hijab (headscarf), I find it very bright, and beautiful”. And with that answer, it was as if she had planted a seed for what was to grow and blossom over the years.

In the mid 90’s, after nailing the role of Um Hasan in the TV series Arabesque, Sultan announced her commitment to wearing the hijab, while continuing to pursue her career in acting. She became a motherly icon, perhaps most memorably cast in the role of Fatima Ta’labah in The Wedge (1996).

This time around, the qualities that shined right through Sultan’s character were her firmness and commitment, which were soon reflected by the way she wore her hijab: neatly, tightly, and simply. Her modest, undecorated headscarves resonated with her strong will, and her determination to start a new chapter.

Even as she grew more religious, Sultan continued to be proud of the legacy she left behind; her rich career in music and cinema would forever remain a cornerstone in her life. Afterall, her various professional and personal experiences serve to prove her intelligence in shaping her unique career.

Even in her motherly roles, Sultan remained an icon of defiance, as she stood for a motherhood that was dignified, confident, and unbound by the patriarchy.

Over the years, Sultan moved with innate grace and acquired modesty, shifting her focus from the bodily pleasures to spiritual bliss.

Posters featured in this article are from City Lights Posters’ Huda Sultan collection, which highlights some of the rarest and most charming posters of the actress.

Noor Hisham Alsaif (noorhishamalsaif.com) is a Saudi fine artist with a Bachelor’s degree in Art Education from King Saud University in Riyadh. Noor participated in group and solo exhibitions in Saudi Arabia and abroad. Her works capture the complex nature of human and social relations. Noor explores such relations from a cinematic perspective, framing her artworks as film scenes with sophisticated narratives. She portrays bold metaphors, converting them into fantasy worlds that evoke self-images and perceptions.

Subscribe to our newsletter to receive the latest latest blog updates, poster releases, and special offers.